Grant’s Story

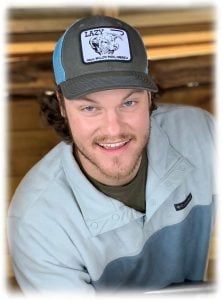

I don’t often mention families or their loved ones by name here; I certainly don’t use their pictures. And if I’m going to tell their story anonymously, I wait long enough that most of you won’t know who they are. But today is different. Today, with his family’s permission, I want to tell you about Grant Johnson. It is their hope, and mine, that by doing so perhaps there are lives that can and will be saved.

This is not a post that will make you feel good; there aren’t any snippets of humor or cynical observations. If that’s what you need or want today, then I suggest you move on without reading this. But if you have children, especially children of driving age, I hope you will read the entire piece . . . and then I hope you will show it to your children and ask them to do the same. And then I hope you’ll talk about what you’ve read and how important it is that they consider the consequences of their decisions—and how many people pay the price when they don’t.

Grant was 23, an age where all the doors of life are opening, where the potential and promise are unlimited—and he was striving to take full advantage of both. He was completing his senior year in college, already employed with the family business and co-owner of his own. He had found the girl with whom he wanted to spend the rest of his life and they had already begun making plans. He had college friends and high school friends and church friends; his circle was wide and ever-growing because Grant had a heart for people. Compassionate and kind, loving and generous, he served as a role model and mentor—a kind of big brother—for the youth group at church, constantly astounding those around him with his knowledge and practice of Biblical principles. His life was coming together in all the ways for which a parent prays. Until the very early morning hours of Sunday, February 3, 2019.

In the darkness of that hour, Grant made a decision . . . a very foolish decision. He wanted to race, and with that decision he handed Death an engraved invitation to not only ride with him, but to take the wheel. It probably wasn’t the first time—and I’m sure Grant thought this time would be like every other time before—but on this night, Death accepted. This time, Grant’s decision cost him his life.

So much died with Grant that night. There will never be a class reunion with his high school friends or the guys with whom he played football and basketball. He won’t be finishing the hard work he started in college or celebrating graduation with his fraternity brothers at MTSU. His friends will no longer have his infectious smile or the mischievous twinkle in his eyes to cheer them up when things are tough, or his listening ear when they just need to confide in someone they trust.

The love of his life now has to struggle with starting her own all over again. And the one person who would have been there to support her in any trial is the person she no longer has . . . the person responsible for the storm she now finds herself trying to navigate. Don’t tell her she’s young and there’ll be someone else. Even if that’s true, it’s of no comfort now. And it never will be. Now there will never be a home built with Grant, a future filled with love and laughter. There will never be the barn they planned to build. There will never be children that bear his name, children to inherit his smile and his wit and his heart for others. For her, that future died with him.

His sister and her husband will never have children that get to play with Uncle Grant or grow up with his children. When her parents leave this earth she will have no one from her immediate family to share birthdays, or Thanksgiving and Christmas, because Grant was her only sibling. There’ll be no gathering and celebrating with her brother and his family . . . her little brother that she fiercely protected as they were growing up . . . the little brother she loved so dearly and deeply. The living connection she would have had to her parents died that night as did all the memories their families would have made together.

Grant’s parents must now walk into a house that is so empty and quiet because he no longer fills every corner. The blessing—and the curse—is that he is still there and always will be. The family pictures and photo albums, his personal belongings, the Christmas stocking that belongs to him . . . what will become of these things and so many more? There will be decisions to make, each one difficult and heartbreaking. Does his stocking get hung this Christmas or does it stay safely packed away? Do they turn his bedroom into something else, something not so filled with memories? Or do they leave it as is so perhaps one day a grandchild will ask to sleep in Uncle Grant’s room . . . the Uncle Grant they never knew . . . the Uncle Grant who is spoken of often with love and longing? Each time they see his picture, it will remind them of what they lost. Each time they walk by his bedroom or see his friends or experience a thousand other tiny moments that will mean nothing to anyone but them, they will remember. They will never get to celebrate his birthday with him again, never get to see him graduate from college or get to watch as he marries and builds a home, never get to rejoice at the birth of his children or celebrate the other milestones of his life. And for the rest of their lives, there will be pain. The severity will lessen with time, there will be more and more moments when life will seem normal again, but there will always be pain.

Grant’s death left a trail of broken hearts and shattered dreams in its wake, touching our community in ways we rarely ever see. As I mentioned at the very beginning of this piece, I hope the parents who have made it this far will sit down with their children and talk with them. Show them Grant’s picture. Tell them his name. Stress to them that it only takes one foolish decision or one distracted moment to turn a mode of transportation into a deadly weapon. Just because they’ve done it before and survived doesn’t mean they will the next time. And if you’re guilty of engaging in any activity that can do the same, then stop. Just stop. Grant’s life and how he lived it to the fullest with compassion and love should be an example for all of us. His death should be a lesson. I hope we choose to learn from both.

About the author: Lisa Shackelford Thomas is a fourth generation member of a family that’s been in funeral service since 1926. She has been employed at Shackelford Funeral Directors in Savannah, Tennessee for over 40 years and currently serves as the manager there. Any opinions expressed here are hers and hers alone, and may or may not reflect the opinions of other Shackelford family members or staff.

The post Grant’s Story appeared first on Shackelford Funeral Directors | Blog.

A Year of Grief Support

Sign up for one year of weekly grief messages designed to provide strength and comfort during this challenging time.

Please wait

Verifying your email address

Please wait

Unsubscribing your email address

You have been unsubscribed

You will no longer receive messages from our email mailing list.

You have been subscribed

Your email address has successfully been added to our mailing list.

Something went wrong

There was an error verifying your email address. Please try again later, or re-subscribe.